by Catherine Travis and Cale Johnstone

Introducing the Sydney Speaks project

Sydney Speaks is a large-scale sociolinguistic project, funded through the ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language (CoEDL 2014-2022) at the ANU, led by Catherine Travis, working with James Grama and Simon Gonzalez (CoEDL post-doctoral fellows (2017-2019)); Katrina Hayes and Cale Johnstone (Project Managers); Benjamin Purser (lead RA); and many RAs who worked on data collection, transcription, and checking vowel alignment.

The Sydney Speaks Corpora

- Contemporary linguistic recordings (collected 2015-present): Sydney Speaks 2010s

- Legacy linguistic recordings (Collected 1977-1981): Sydney Social Dialect Survey

- Legacy oral histories (collected 1987-1988): NSW Bicentennial Oral History Collection

Data access concerns

Combining legacy and contemporary data collections

References

Sydney Speaks Corpus and Publications

Since 2015, the Sydney Speaks project has recorded the spontaneous speech of Sydneysiders for the purpose of documenting and exploring Australian English as spoken in Australia’s largest and most ethnically and linguistically diverse city. In order to study language change in real-time, the project also incorporates legacy data from two sources: a sociolinguistic project carried out in the late 1970s and an oral history collection created during the 1980s. Altogether, the birth years of the participants span over a century, from the 1890s to the 1990s, and five age groups are represented, as captured in Figure 1.

Image Source: Catherine Travis

Each of the three sub-corpora of Australian English presents a different set of challenges and issues for data management practices that maximise the value of the data, while protecting the ethical, moral and legal rights of the participants. Below, we present each sub-corpus individually, and provide a summary of each sub-corpus. We describe the ways in which recordings were made and transcription was managed; outline how we were able to get comparable demographic information from participants when this was not standardised across the corpora; and detail how we dealt with participant consent and privacy. We close by reviewing a set of data access concerns around de-identification, data security and access and re-use.

In this overview of the process by which different datasets collected for distinct purposes and under varying conditions have been brought together to constitute a coherent corpus of language data, we hope to highlight some of the considerations key to working with sociolinguistic data, and the enormous potential for the incorporation of other data sources through the use of appropriate standards for data management.

The Sydney Speaks corpora

Contemporary linguistic recordings (collected 2015-present): Sydney Speaks 2010s

Sub corpus overview

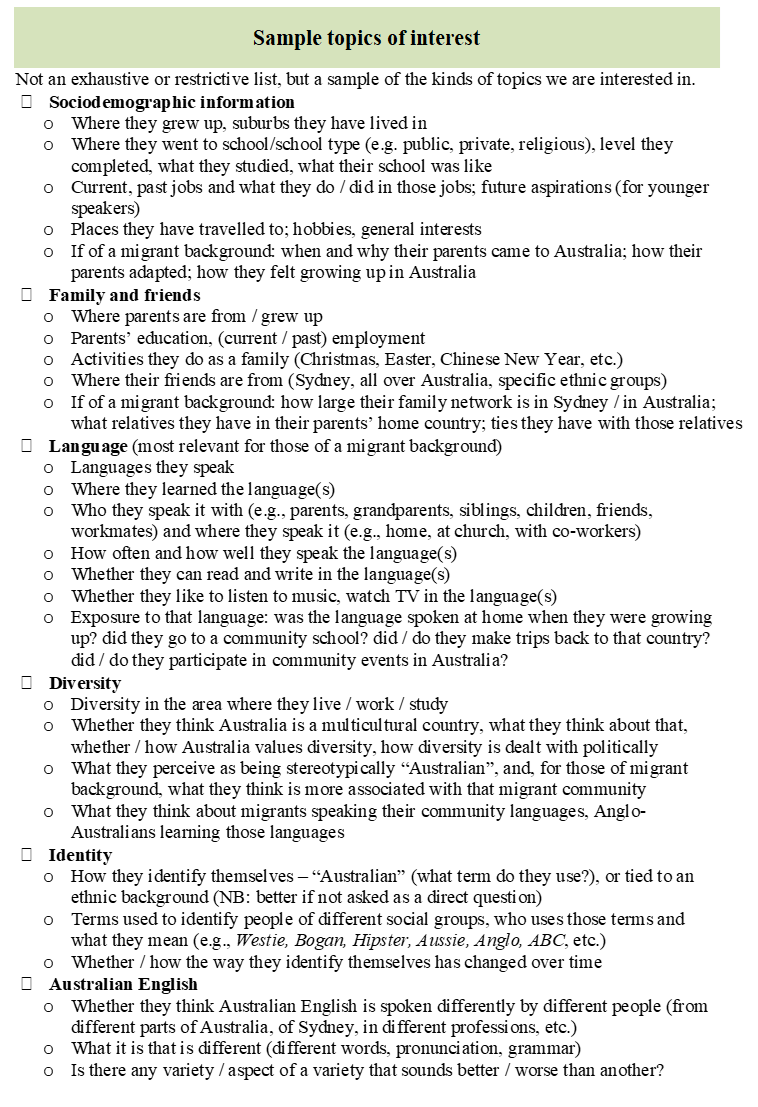

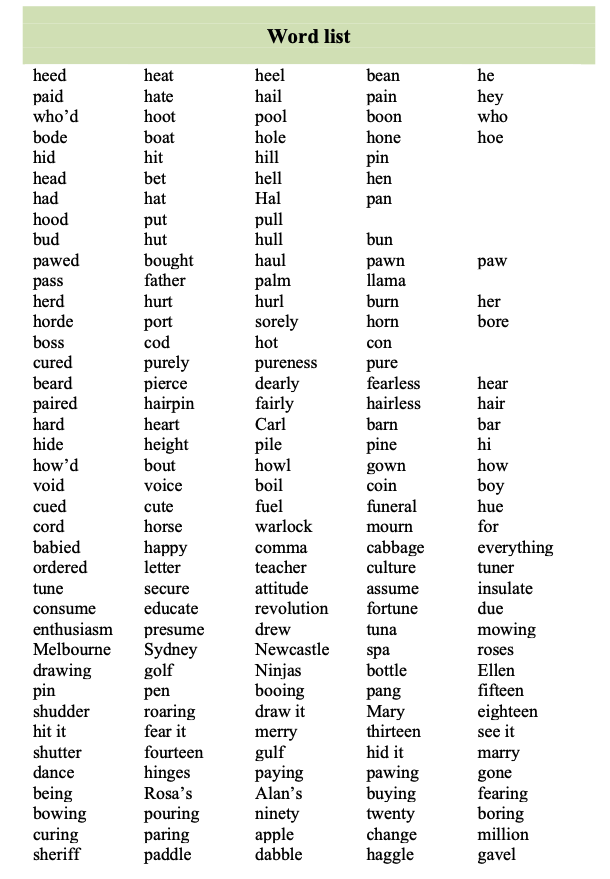

The Sydney Speaks 2010s sub-corpus comprises recordings made from 2015 to the present. Data collection is still ongoing, but as of June 2023, Sydney Speaks 2010s comprises 142 sociolinguistic interviews with men and women of varying ages from different ethnic communities in Sydney representing some of the largest ethnic minorities in Australia, namely Anglo-Celtic, Chinese, Greek, and Italian Australians. The interviews were generally conducted individually (though some were done in pairs), and they were conducted by community members, typically with people they knew. The interviewers were provided with a list of suggested topics, covering such things as childhood memories, growing up in Sydney, school and work experiences, and for the Greek, Italian and Chinese participants, engagement with their ethnic community and language, but they were told to use these as a guide only, and to follow the participants’ lead in choosing topics. Thus, the data is highly interactional, in some cases conversational, and topics vary greatly across recordings. There is a focus on recording narratives of personal experience, as these have been demonstrated to be particularly ideal for recording the everyday vernacular (Labov 1984:32-42). After the sociolinguistic interview, participants read aloud a word list, which provides a comparison for both the sociolinguistic interview data and other studies of Australian English (as many have focused on read word lists). The suggested interview topics and the word list are given in Figures 2a and 2b.

Image Source: Catherine Travis

Image Source: Catherine Travis

Recordings and transcripts

Interviews are recorded using a Zoom H4N digital recording device in WAV format at 44.1 kHz/16 bits. They are orthographically transcribed, aligned at the utterance level and then uploaded into LaBB-CAT (Language, Brain and Behaviour Corpus Analysis Tool (Fromont & Hay 2012)), for forced alignment (which automates the process for alignment at the level of the phoneme). LaBB-CAT also serves as the corpus management tool, where the corpus is stored, data is further annotated, and concordance searches can be conducted. LaBB-CAT does not include corpus analysis tools as such, but data can be downloaded in multiple formats to allow for analyses, including CSV and WAV, as well as in formats that are compatible with tools that are used widely by linguists, such as ELAN, illustrated in Figure 3 (Lausberg & Sloetjes 2009) and Praat in Figure 4 (Boersma & Weenink 2019).

![Sample SydS transcript in ELAN, time aligned at the level of the Intonation Unit [SydS_CYM_061_Mark] Sample SydS transcript in ELAN, time aligned at the level of the Intonation Unit [SydS_CYM_061_Mark]](/sydney-speaks/fig-3.png)

Image Source: Catherine Travis

![Sample SydS transcript in Praat, downloaded from LaBB-CAT, where it has been automatically aligned at the level of the word and phoneme, and broken down by morpheme [SydS_CYM_061_Mark] Sample SydS transcript in Praat, downloaded from LaBB-CAT, where it has been automatically aligned at the level of the word and phoneme, and broken down by morpheme [SydS_CYM_061_Mark]](/sydney-speaks/fig-4.png)

Image Source: Catherine Travis

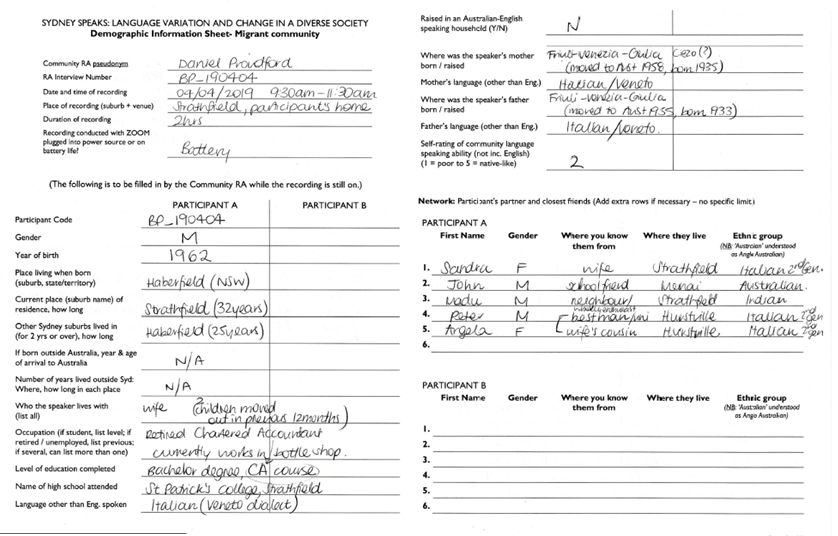

Participant metadata

Detailed speaker metadata is collected via a demographic form that includes information such as place and year of birth, current and past suburbs of residence, occupation, education, community background, languages, and social networks (see Figure 5). This questionnaire is conducted orally at the end of the interview (as a continuation of the interview), and the participants’ responses are filled in by the interviewer. Information is extracted from the written form, validated in the recorded audio, and added to a metadata spreadsheet in Excel. We use customised metadata, rather than drawing on a standard metadata vocabulary; however the demographic information from each sub-corpus is standardised in Excel and comparable across the three sub-corpora.

Image Source: Catherine Travis

Participant consent and privacy

The Sydney Speaks contemporary data collection process follows the guidelines of an ethics approval obtained from the Australian National University (Protocol #2015-088). In accordance with these guidelines, written consent is obtained for each participant prior to the recording. The participant is provided with information about the project, including the general topic of study (Australian English across different communities), project funding, ethical considerations such as confidentiality and data storage, and direct contact information for the research team.

Participants are told that the data may be shared, with approval from the lead researcher, and they are asked to sign a written consent form, offering them different options along a continuum from solely participating in the project and having their voice recorded, to having their data shared in various settings, as presented in Figure 6. The vast majority of participants gave full consent (136 out of 142 total participants recorded), and only one person agreed only to participate in the project, but for there to be no further access of their materials (two chose not to have their audio played in public; two didn’t want their data available for other researchers; and four didn’t want recoding in web-based corpora).

Image Source: Catherine Travis

Legacy linguistic recordings (Collected 1977-1981): Sydney Social Dialect Survey

Horvath, Barbara. 1985. Variation in Australian English: The sociolects of Sydney. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Sub-corpus overview

The Sydney Social Dialect Survey (SSDS) is a collection of 177 sociolinguistic interviews with adult and teenage Australians from Anglo-Celtic, Greek, and Italian backgrounds, recorded in Sydney between 1977 and 1980, as part of an ARC-funded project led by Barbara Horvath, of the Department of Linguistics at the University of Sydney. For the Sydney Speaks project, recordings from Anglo-Celtic adults (born in the 1930s) and from Anglo-Celtic, Greek and Italian Teenagers (born in the 1960s) were included. The recordings with Greek and Italian adults were set aside, as they arrived in Australia as adults and speak English as a second language, and thus raise a different set of questions for the study of language variation and change. There were 7 participants who did not meet the Sydney Speaks participant criteria (e.g. one of their parents was not of the target ethnic groups), leaving a total of 20 adults and 72 teenagers for inclusion. Like the contemporary linguistic data, the Sydney Social Dialect Survey comprises sociolinguistic interviews, but these are more interview-like: the interviewers were not community members, and they did not typically know the participants; and the topics were more defined (some common topics being games, layout of the school, nicknames, and language).

Recordings and transcripts

Interviews were conducted in the 1970s with a cassette recorder and made available to the Sydney Speaks project directly by the lead researcher. The audio cassettes, type-written transcripts, and demographic information of the participants were stored in boxes in Horvath’s garage in Sydney and passed on to Catherine Travis in 2013. The cassettes (pictured in Figure 7) were digitised using PARADISEC equipment in the College of Asia Pacific Studies at the ANU to create WAV files (96.1 kHz, resampled using Audacity into smaller files of 44.1 kHz). Fortuitously, the cassettes had been preserved very well, and nearly all of them (124/130) were able to be digitised, and with further refinement, it was possible to conduct acoustic analyses (though in some cases, this presented considerable challenges that did not arise with the new recordings). The typewritten transcripts were scanned and digitised as PDFs, but it was not possible to convert them into machine-readable transcripts, partly because they had been marked up by hand for transcript corrections, coding and annotation, as can be seen in the sample in Figure 8. They were therefore re-transcribed in ELAN by the Sydney Speaks team, following the protocols applied for the contemporary data (see sample ELAN rendition of part of Figure 8 in Figure 9).

Image Source: Catherine Travis

![Sample SSDS transcript with annotations [SSDS_ITF_120_Sara] Sample SSDS transcript with annotations [SSDS_ITF_120_Sara]](/sydney-speaks/fig-8.png)

Image Source: Catherine Travis

![Sample SSDS transcript time-aligned in ELAN [SSDS_ITF_120_Sara] Sample SSDS transcript time-aligned in ELAN [SSDS_ITF_120_Sara]](/sydney-speaks/fig-9.png)

Image Source: Catherine Travis

Participant metadata

Metadata for each speaker was extracted from original type-written profiles that included information such as suburb, date of birth, age, occupation, education, languages, and time lived in Sydney (see Figure 10). Details were standardised and added to the project metadata database in an Excel spreadsheet. Further demographic information was added from several other sources, including participant overview documents put together by the lead researcher, original cassette labels as well as from the audio recordings themselves. We were not able to extract the same demographic information for all participants, and we have more details for some than for others, something which needs to be taken into account in cross-corpus comparisons.

Image Source: Catherine Travis

Participant consent and privacy

Data collection for the Sydney Social Dialect Survey was completed during the 1970s and 1980s. No ethics approval process was required at the time and documentation for participant consent was not sought. Approval was obtained from the ANU HREC to use the data for the Sydney Speaks project. In accordance with the guidelines of that approval, the team has undertaken an exhaustive process to anonymise all content that may indicate the identity of a participant in the metadata, audio, and transcripts. In addition, it is likely that the voices of the participants, and particularly the teenage speakers, will have changed significantly in the 45 years since the interviews were conducted.

Legacy oral histories (collected 1987-1988): NSW Bicentennial Oral History Collection

NSW Bicentennial Oral History Project. 1987. NSW Bicentennial oral history collection. Council on the Ageing NSW Branch and NSW Oral History Association of Australia, housed at the National Library of Australia.

The process of conducting oral history involves recording interviews to collect information about the past, from the perspective of those who lived through relevant events. In recording everyday voices, oral histories are particularly valuable for research across Humanities disciplines as they capture the ‘little-heard voices of society’. They are of particular value for linguistic analysis, because they aim to ensure that ‘the historical record includes different languages and vernacular speech, accent and dialect’ (Oral History Statement of value; What is oral history? Retrieved May 23, 2022, from Oral History Australia). Like the sociolinguistic interview, oral histories elicit narratives of personal experience, and thus they provide highly comparable data.

Sub-corpus overview

The NSW Bicentennial Oral History Collection, produced by the NSW Bicentennial Oral History Project, comprises 200 interviews recorded in 1987 and 1988 with men and women born before 1910. The Sydney Speaks project has incorporated 31 interviews with people who were born in Sydney and whose parents were also born in Sydney. The recordings include discussions about life in Sydney in the early part of the twentieth century, including the war, women’s first experience in the workforce, the outbreak of the Spanish flu, and so on. The collection is managed by the State Library of NSW and the National Library of Australia. In 2017, the Sydney Speaks project gained access to the collection via direct request to the National Library of Australia.

Recordings and transcripts

The original audio of each interview was recorded on cassette tape and was made available to the Sydney Speaks team in MP3 and WAV format, allowing for acoustic analysis. Type-written transcripts (Figure 11) were also made available, from which the Sydney Speaks team was able to create machine-readable versions via OCR (Optical Character Recognition). The original transcript captured the content very accurately, and this was imported into ELAN and edited to produce detailed transcriptions that are aligned with the audio and facilitate linguistic analysis (Figure 12).

![Sample transcript from Bicentennial Oral History Project [BCNT_AEF_032_Camila] Sample transcript from Bicentennial Oral History Project [BCNT_AEF_032_Camila]](/sydney-speaks/fig-11.png)

Image Source: Catherine Travis

![Sample Bicentennial Oral History Project transcript time-aligned in ELAN [BCNT_AEF_032_Camila] Sample Bicentennial Oral History Project transcript time-aligned in ELAN [BCNT_AEF_032_Camila]](/sydney-speaks/fig-12.png)

Image Source: Catherine Travis

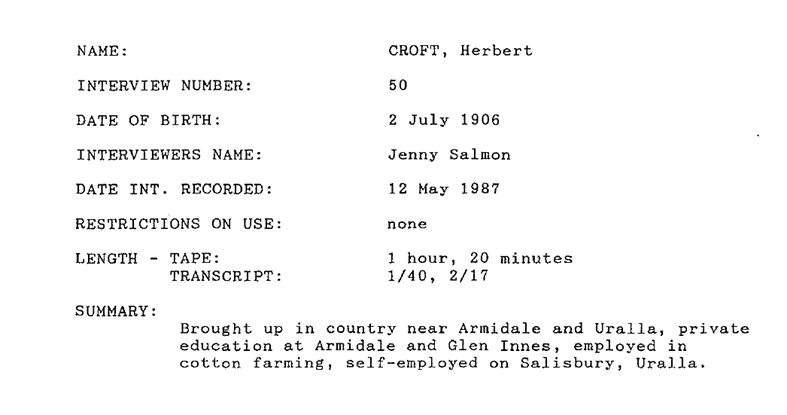

Participant metadata

Demographic data was collected at the time of the interview for each participant; this included name and date/place of birth as a minimum, but a ‘summary’ provided further information, such as parents’ education and occupations, employment (past and current), interests and marital status (see sample in Figure 13). The recordings themselves also provided a wealth of demographic information, as is common practice in oral histories, meaning that full demographic profiles could be developed for most participants. Some investment is necessary to capture and systematise this information, but its availability is one of the clear advantages they have for (socio)linguistic analysis.

Image Source: Catherine Travis

Participant consent and privacy

Incorporating speech data from oral history collections is new ground for linguistic research and there are no existing guidelines to follow regarding the consideration of participant consent. The NSW Bicentennial Oral History Collection manual indicates which ‘restrictions on use’ were sought by the participants. A small number of participants asked for their name not to be used and for permission to be sought before publication of the data. For most of the collection, participant names and basic demographic information is publicly available. None of the participants who are included in the Sydney Speaks collection had placed restrictions on the use of the data. In accordance with contemporary ethical practice, however, the Sydney Speaks project has anonymised speaker names and other identifying content in the audio and transcripts as was done for the other sub-corpora.

Data access concerns

De-identification

All speakers have been given pseudonyms, for which we aim to parallel the original name (thus, Sarah may be Sally, Alfredo may be Alberto etc.). In the transcripts themselves, names and all other identifying content (such as addresses, school names, nicknames, etc.) have been de-identified in all data formats. In the transcripts, this is done by using pseudonyms, for readability purposes (rather than noting [XXX], or [pseudonym], for example). To indicate to the analyst what words are pseudonyms, all pseudonyms are marked (preceded by a tilde, e.g. ~Jane, ~Millers ~Point). For the audio, we identify the segment that needs de-identification, and run a low-pass filter using a Praat script so that the name is not recognisable.

During an interview, some participants have requested that a section not be included in the study, generally due to what they perceive to be the sensitive nature of a certain topic (for example, one participant talking about banking in Hong Kong). In these cases, this portion of the recording has been deleted, and it has not been transcribed or included in any analysis.

Data security

Data security measures are guided by the Sydney Speaks ethics approval. Long-term storage is especially important for legacy data that hasn’t been digitised or archived where data loss is a realistic risk.

Contemporary data is collected in Sydney and transferred to the research team based at the ANU in Canberra. A remote data transfer system using an online cloud service ensures the safe transfer of raw data. Original audio and transcripts in the possession of the project are stored in a locked cabinet, managed by the project lead. Data has been digitised to secure the collection long term, and it is stored in an online cloud service as well as backed up on external hard drives. Having multiple copies of the data increases the security of the collection and using pseudonyms in the file naming protocols protects the identity of participants.

Data access and reuse

In accordance with the project ethics protocol, the data is made available to other researchers with the approval of the Sydney Speaks project lead, Catherine Travis. While data from the NSW Bicentennial Oral History Collection is openly accessible online, the agreement between the National Library of Australia and the Sydney Speaks project allows the Chief Investigator to determine future access to the data from the subset of speakers included in the Sydney Speaks collection, with the condition of correct attribution. The Sydney Social Dialect Survey legacy data was transferred to the Sydney Speaks in full, including the capacity to make decisions about data access and reuse.

Regular outreach activities such as presentations, workshops, public lectures and publications, promote the corpus and increase awareness of the data. The corpora are also described on lists of significant language data collections, such as the Sydney Corpus Lab Blog. They are stored with the DOI managed through the library at the Australian National University: https://dx.doi.org/10.25911/m03c-yz22.

Access to the Sydney Speaks collection (including all three sub-corpora) is managed on a case-by-case basis. There is an agreed-upon set of terms and conditions for use of the collection, to ensure that any use is in accordance with the ethics approval, and these conditions are specified in the data access licenses developed with support from the Language Data Commons of Australia (LDaCA). Users must fill in an online application form, specifying how the corpora will be used and guaranteeing appropriate attribution to gain access.

Combining legacy and contemporary data collections

In the past, language data was often collected without much consideration of the use of that data beyond the specific purpose for which it was collected. Issues such as ethics, data storage, and long-term data management plans were not of primary concern in the way that they are today, when we are guided by the FAIR principles around Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Re-usability. This does not mean, however, that older language collections (or collections made from other disciplines and for other purposes) cannot be made FAIR. The Sydney Speaks project has demonstrated that legacy corpora can be brought into line with standards appropriate for data in the current digital age. Integrating contemporary and legacy data collections in this way allows for an upscaling of our studies in both the size and the scope of the language data we work with, and in so doing can open a treasure trove of knowledge on Australian language, society, culture, and history.

References

Boersma, Frederic, J. and D. Weenink. 2019. Praat: Doing phonetics by computer [Computer Software] (6.1.03 ed.): Retrieved 1 September 2019 from http://www.praat.org/.

Fromont, Robert and Jennifer Hay. 2012. LaBB-CAT: An annotation store. Proceedings of the Australasian Language Technology Workshop: 113-117.

Labov, William. 1984. Field methods of the project on linguistic change and variation. In John Baugh, and Joel Sherzer (eds), Language in use: Readings in sociolinguistics, 28-53. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Lausberg, Hedda and Han Sloetjes. 2009. Coding gestural behavior with the NEUROGES-ELAN system. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers (Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, The Language Archive, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. http://tla.mpi.nl/tools/tla-tools/elan/). 41(3): 841-849.

Sydney Speaks Corpus and Publications

Travis, Catherine E., James Grama, Simon Gonzalez, Benjamin Purser and Cale Johnstone. 2023. Sydney Speaks Corpus. ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language, Australian National University. https://dx.doi.org/10.25911/m03c-yz22

Gonzalez, Simon, James Grama and Catherine E. Travis. 2020. Comparing the performance of forced aligners used in sociophonetic research. Linguistics Vanguard 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1515/lingvan-2019-0058

Grama, James, Catherine E. Travis and Simon Gonzalez. 2019. Initiation, progression and conditioning of the short-front vowel shift in Australian English. In Sasha Calhoun, Paola Escudero, Marija Tabain, and Paul Warren (eds), Proceedings of the 19th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences (ICPhS), Melbourne, Australia, 1769-1773. Canberra, Australia: Australasian Speech Science and Technology Association Inc. https://assta.org/proceedings/ICPhS2019/papers/ICPhS_1818.pdf

Grama, James, Catherine E. Travis and Simon Gonzalez. 2020. Ethnolectal and community change ov(er) time: Word-final (er) in Australian English. Australian Journal of Linguistics 40(3): 346-368. https://doi.org/10.1080/07268602.2020.1823818

Grama, James, Catherine E. Travis and Simon Gonzalez. 2021. Ethnic variation in real time: Change in Australian English diphthongs. In Hans Van de Velde, Nanna Haug Hilton, and Remco Knooihuizen (eds), Studies in Language Variation, 292-314. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://www.jbe-platform.com/content/books/9789027259820-silv.25.13gra

Lee, Esther. 2020. Quotatives over time: A study in ethnic variation. Honours thesis, School of Literature, Languages and Linguistics, Australian National University. http://hdl.handle.net/1885/298816

Purser, Benjamin, James Grama and Catherine E. Travis. 2020. Australian English over time: Using sociolinguistic analysis to inform dialect coaching. Voice and Speech Review 14(3): 269-291. https://doi.org/10.1080/23268263.2020.1750791

Qiao, Gan and Catherine E. Travis. 2022. Ethnicity and social class in pre-vocalic the in Australian English. In Rosey Billington (Ed.), Proceedings of the Eighteenth Australasian International Conference on Speech Science and Technology (pp. 56-60): Australasian Speech Science and Technology Association. https://sst2022.files.wordpress.com/2022/12/qiao-travis-2022-ethnicity-and-social-class-in-pre-vocalic-the-in-australian-english.pdf

Sheard, Elena. 2022. Longevity of an ethnolectal marker in Australian English: Word-final (er) and the Greek-Australian community. In Rosey Billington (Ed.), Proceedings of the Eighteenth Australasian International Conference on Speech Science and Technology (pp. 51-55): Australasian Speech Science and Technology Association. https://sst2022.files.wordpress.com/2022/12/sheard-2022-longevity-of-an-ethnolectal-marker-in-australian-english-word-final-er-and-the-greek-australian-community.pdf

Sheard, Elena. 2023. Explaining language change over the lifespan: A panel and trend analysis of Australian English. PhD thesis, School of Literature, Languages and Linguistics, Australian National University. http://hdl.handle.net/1885/292110

Travis, Catherine E., James Grama and Benjamin Purser. 2023. Stability and change in (ing): Ethnic and grammatical variation over time in Australian English. English World-Wide 44(3): 429-463. https://doi.org/10.1075/eww.22043.tra

Travis, Catherine E. and Rena Torres Cacoullos. 2023. Form and function covariation: Obligation modals in Australian English. Language Variation and Change 35(3): 351-377. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394523000200.