by Simon Musgrave

My article on Australian Slang as a literary genre has recently been published by the Australian Journal of Linguistics and four datasets from the Language Data Commons of Australia (LDaCA) collection are cited there. Although the results derived from that data are covered in a few sentences (in an 8000 word piece), access to the data was crucial for me in making a strong argument. This post is intended to show how that was the case, and therefore why infrastructure such as LDaCA is valuable to researchers.

Some background

The first part of my argument in the article is that there is a tradition of Australian writers inventing expressions which they then treat as being part of Australian slang - and people who know Australian English accept such expressions as being part of the language even if they are scarcely used outside of the original works. For example, most of us in Australia (well, over a certain age anyway!) will recognise the expression technicolour yawn and may even associate it with Barry Humphries’ creation Barry McKenzie. But what sort of evidence is there of people actually using the phrase?

Image Source: Simon Musgrave

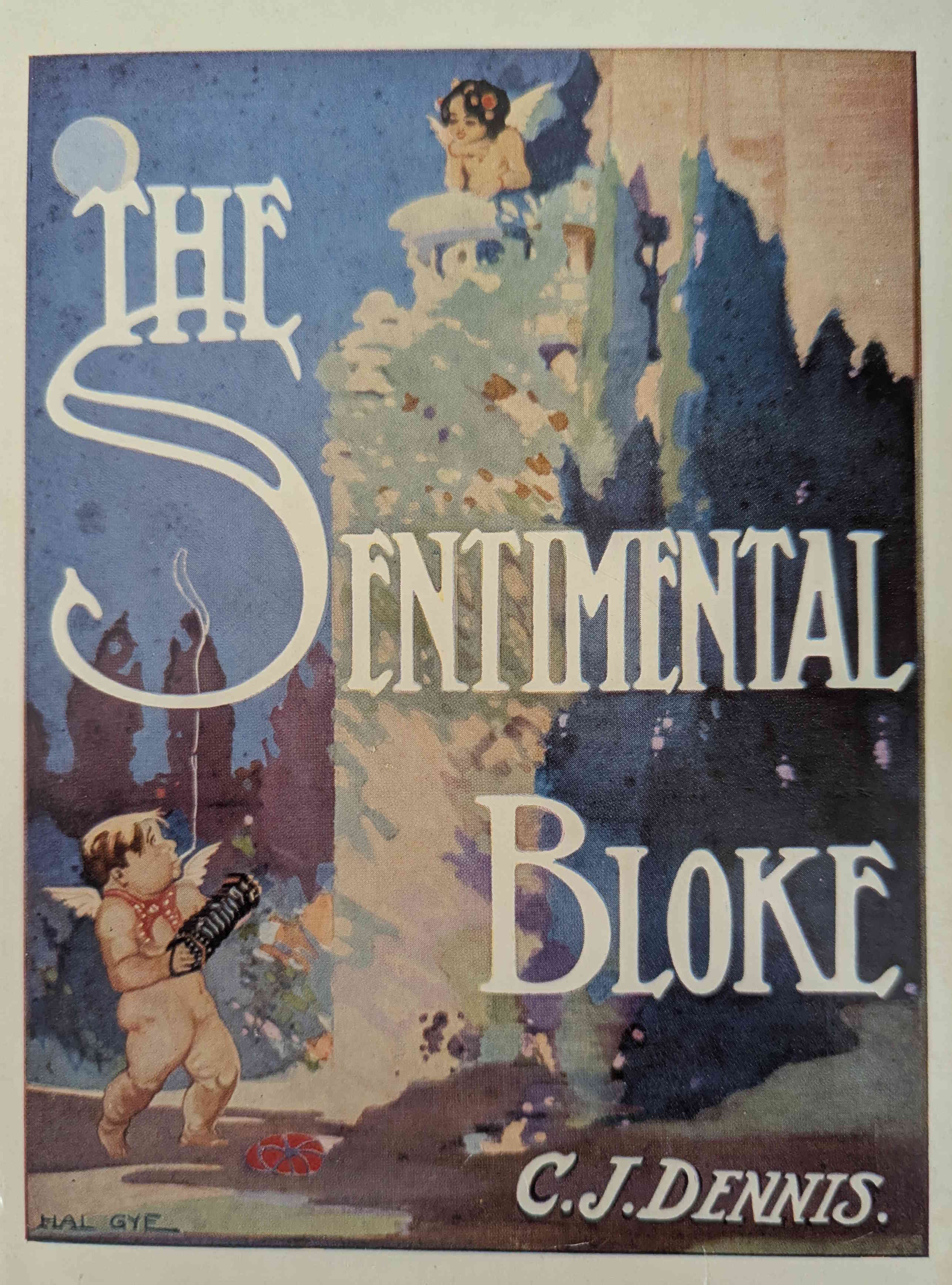

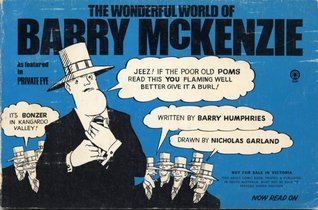

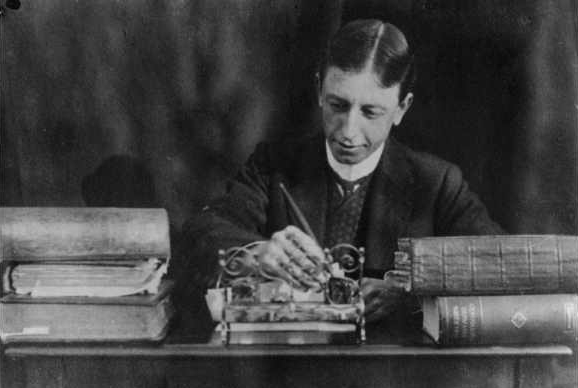

In the article, I examine three examples of this type of slang: the language which C.J.Dennis attributes to his Sentimental Bloke, the language of Barry McKenzie, and the language presented by the writers of The Betoota Advocate in their 2021 book Betootaisms. The case of Dennis is a little different to the other two. We have very little evidence of how people spoke in Australia (specifically in Melbourne) early in the 20th century and it is therefore not possible to make the case that Dennis used expressions which he invented rather than ones which he observed (but I think I nevertheless make a reasonable case that his work is part of a tradition which encompasses the other two examples). For Betootaisms, it is easy to use web search engines to look for evidence of usage (spoiler alert: there is little such evidence outside of the pages of The Betoota Advocate). But what about Barry McKenzie? The character was created in 1964 and was perhaps most prominent in the 1970s, when two films were made centred on him. I needed data showing language used in Australia later than that period so that I could check whether the expressions used by Barry McKenzie had a wider currency or not.

Image Source: https://www.betootaadvocate.com/

My first attempt

The cover of the first Barry Mackenzie book has words attributed to the hero and to a group of other men who we can assume to also be Australians in London. Included in those words are four which might be considered as Australian slang: jeez, poms, burl and bonzer. I looked for these words and also the expressions technicolour yawn and chunder in a large corpus of Australian newspaper articles compiled by linguists at Lancaster University’s Corpus Approaches to Social Science Research Centre consisting of nearly 13,000 articles and close to 7.4 million words. The data comes from 18 Australian newspapers and includes all news articles published over 12 months from August 2015 to July 2016 that contained one of the following keywords: Australia, Australian, or Australians (more details can be found in an article in The Conversation by Annabelle Lukin of Macquarie University). Unfortunately, this collection cannot be shared for copyright reasons - we would love to include it in LDaCA - but I happen to have a copy (for personal study only, of course).

Image Source: Simon Musgrave

Searching for the words mentioned above in this corpus gave the following results:

In the newspaper corpus, jeez occurs twice, poms occurs 16 times, and burl and bonzer do not appear at all. As noted above, the expression technicolour yawn is recognized by many as Australian slang, but it also does not appear in this corpus. Looking at another word for vomiting which Barry McKenzie uses frequently, chunder, we find a single instance which is an indirect reference to the original meaning:

Reflecting on the Thunder’s unlikely run to this season’s final, Khawaja revealed there were times during the club’s lean years when he asked himself whether he wanted to be in a team derided as “The Chunder” and considered the competition’s basket case. (The Sydney Morning Herald, 23/01/2016, p. 53)

This last word chunder is particularly interesting because its history has been traced outside the work of Barry Humphries. It certainly existed before Barry McKenzie used it - see Greens’ Dictionary of Slang. Indeed, Humphries relates that he learned it at school (as recounted by Bruce Moore (2010, p. 42). Green’s dictionary has citations up until 2016, but the newspaper data suggest that it is losing currency. In the corpus, the synonyms vomit and spew have four and two instances, respectively.

Image Source: Wikimedia

In the version of my article submitted for review, I used these results to argue that there was little evidence that the language Barry Humphries had attributed to Barry McKenzie was actually used in Australian English. The article was part of a special issue of the journal, which meant that my submission was reviewed by the special issue editors (Isabelle Burke and Dylan Hughes) and an external reviewer. The comments of the external reviewer were sympathetic and helpful and included a query as to whether I had in fact sufficiently made the case for the absence of the relevant expressions from actual language use. Thinking about this again, I realised that the query was legitimate: the time gap between the heyday of Barry McKenzie and the data I looked at was too great. I needed to look at earlier data from the last two decades of the 20th century, if possible.

LDaCA to the rescue!

The Language Data Commons of Australia has three collections of data which were relevant to my needs:

- The Australian Corpus of English was compiled to match Australian data from 1986 with the American (Brown) and British (Lancaster-Oslo-Bergen) corpora of written English from the 1960s. It includes 500 samples of published texts taken from 15 different categories of nonfiction and fiction, including newspapers, reportage, editorials, reviews, magazines and journals: popular, academic; government and corporate documents; fiction monographs and short stories (both popular and literary).

- The Australian component of the International Corpus of English is an approximately one million word corpus of transcribed spoken and written Australian English from 1992-1996. It consists of 500 samples of Australian English (60% speech, 40% writing) that matches the structure of other ICE corpora (associated with the International Corpus of English). The spoken data includes recordings and transcriptions of face-to face spoken conversations, telephone conversations, monologues, broadcast dialogues, and scripted speech. The written texts include samples of unpublished letters (personal and professional), student essays, newspaper writing, popular nonfiction, academic writing, and fiction.

- Australian Radio Talkback includes 14 transcribed recordings of talkback from ABC National Radio, ABC Radio broadcasts to eastern Australia, and ABC Radio broadcasts to southern and western Australia; as well as 15 transcribed recordings of talkback radio from commercial stations broadcasting to eastern Australia and southern and western Australia. The material was collected in the early 2000s.

Each of these collections was previously part of the Australian National Corpus (AusNC) - this post explains the historical relationship between AusNC and LDaCA.

I was able to conduct searches across these sources which confirmed my hypothesis that there is little evidence for actual use of the expressions Humphries put in the mouth of Barry McKenzie. I wrote the following in the article - it is clear that some of the absences are due to the effect of time, but I don’t think that such effects account for all the gaps:

Searching these sources for the four terms used on the cover of the first Barry McKenzie book finds 11 hits for jeez (of which one is in another collection and dates from 1936), eight hits for pom and poms, two hits for bonzer/bonza (of which one is a metalinguistic comment), and no hits for burl. Chunder and technicolour yawn are both absent from these sources.

Searching these data sources available through LDaCA made me confident that many of the words Barry McKenzie uses are not commonly used in Australia and strengthened the argument I had presented in the earlier version.

Slang turns sour

It was a lot of fun exploring the language used by these writers; all of them can be very funny. For example, Dennis defines hang-over as ‘the aftermath of the night before’, Humphries defines armful of chairs as ‘Something some people would not know whether you were up them with or not with’ and Betootaisms defines sunburnt sudoku as ‘The boat ramp, A needlessly complicated stretch of concrete surrounded by great minds’. But the fun didn’t last for me.

Image Source: Public domain

Some of the questions which I tried to answer in the article are why it is that these literary expressions which are not being used in everyday speech are nevertheless recognised by many speakers of Australian English and why do we find it easy to imagine that a dinkum Aussie could use them. The argument which I develop is that the three sources reflect a set of values which are quite consistent over the more than 100 years covered by my sample. All of them share attitudes to ethnic and cultural background, gender and relations between the sexes and to the use of alcohol, and what is (at least implicitly) expressed is not encouraging. As I say in the abstract of the article, there are “recurring themes across this 100-year tradition, showing that the world in which this language is grounded is one where white males who like alcohol are prominent”.

I referred to another dataset from LDaCA in discussing the relative absence of Indigenous Australians from the language I was investigating. The Betoota Advocate purports to represent the opinions and world view of a rural community in the Channel Country of western Queensland. To highlight how Indigenous people were represented in Betootaisms, I was able to make a comparison with the oral history material from the same location in the Braided Channels collection (also listed in LDaCA).

Despite the somewhat depressing conclusion above, I hope that this account of my research gives you an idea of how research infrastructure such as LDaCA can assist the process of research. I used the data from LDaCA to resolve a small question in the development of my argument, but having the answer to that small question was an essential step in building what I hope is a convincing position. Not having easy access to the data would have meant spending a lot of time looking for alternative sources or having a weak link in my argument. I am very happy that I did not have to accept either of those possibilities.

Reference: Moore, Bruce. 2010. What’s their story? a history of Australian words. South Melbourne, Vic: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgments: Thanks to Bridey Lea and Jo Savill for helpful editing suggestions. The work I describe here was supported by the Australian Research Council’s Special Research Initiatives under grant number SR200200350 Metaphors and Identities in the Australian Vernacular and would not have been possible without the other members of the Monash Slang Gang: Kate Burridge, Howie Manns, Isabelle Burke, Dylan Hughes and Keith Allan.