by Maria Weaver

We have learned from conversations with data stewards over the last two years that some are new to the practice of using persistent identifiers (PIDs) for data collections. This blog post will hopefully offer some guidance by briefly providing some background information and addressing the common questions we receive about PIDs and Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs).

A brief overview of persistent identifiers

Most of us are familiar with the concept of identifiers (IDs); they mark and individualise a person through life, from their name at birth through to IDs assigned at school, at work and in other contexts. Identifiers are needed for countless things in complex societies, e.g. material goods, documents and transactions, but the purpose remains the same: to unambiguously identify someone or something among similar others within a context.

As far as we can see in the literature, the term PID is closely tied to the rise of the internet and digital information management in the 1990s. This makes sense as PIDs are meant to operate in the context of the web environment. The qualifier “persistent” refers to the need to mitigate effects of the transient nature of online content, where websites and digital resources can disappear, change or become inaccessible over time (Chapekis et al. 2024).

PIDs are a critical part of scholarly communication, especially online where the volume of data is increasing every minute. Research outcomes and resources have to be shared appropriately, therefore, data objects and entities need to be unambiguously identifiable and reliably findable, and the connections between them made evident. PIDs are fundamental to fulfilling these requirements. The Australian Research Data Commons’s Australian National PID Strategy 2024 provides an excellent summary of how PIDs contribute to strengthening the digital infrastructure ecosystem and to driving research innovation in Australia.

A strategy used by some PID systems (e.g. the DOI system) to sustain persistence is separating how the object is identified from where the object is located. The identification component consists of a globally unique identifier; a typical convention is as a series of numbers, letters and special characters. This identifier is optimised on the web by being actionable, that is, it can be formatted as a locator, e.g. a URL, that points to information or metadata about the object (also referred to as the reference to the object). Based on this strategy, an identifier is considered persistent when it consistently resolves over a reasonably long period to the webpage containing information or metadata about the object, including information about the location of the object.

The location component is where the object is served or made available, whether on the web or in the physical world. Should the object location change, e.g. a data collection is moved to a different repository or becomes available through other websites, the relevant metadata on the reference page should reflect that fact. Note that although the reference is a digital description, it can be a description of any object or entity, whether digital, physical (e.g. scientific specimens, cultural heritage objects) or abstract (e.g. software, organisations).

Understandably, PID systems on a global scale require large investments in robust technological infrastructures, including geographically distributed servers, digital preservation, and redirection and resolver systems. However, such infrastructure is useless without people and social structures to ensure that PIDs work as expected for as long as possible. Organisational commitment from stakeholders, including data owners, repository managers and PID registration agencies, are vital. Data stewards, for example, are responsible for obtaining PIDs for their datasets, creating rich and accurate metadata, ensuring changes to the metadata and the dataset are reflected in the PID registry, and adhering to data governance best practices, community standards and protocols.

The PID landscape continues to evolve. If you are interested in delving deeper into persistence strategies used by different PID systems or nuanced views of identifier persistence from experts, see the Further Reading items below.

Below are a few examples of PIDs within digital scholarly ecosystems:

- DOI (Digital Object Identifier) — PID for research objects, e.g. academic journal articles, datasets, books, code, media. DOIs are discussed further in the question-and-answer items below.

- ORCiD (Open Researcher Contributor ID) — A registry providing globally unique identifiers for researchers, authors and contributors of scholarly works. Registered users can use the same ID right through their career, with it persisting through name changes and geographic or organisational relocations.

- ROR (Research Organization Registry) — A global, community-led registry of open persistent identifiers for research organisations. Allows anyone or any system to disambiguate institution names, and connect research organisations to researchers and research outputs.

- The Handle System — A proprietary registry of the Corporation for National Research Initiative (CNRI) that assigns PIDs (“handles”) to information resources in distributed computer systems. It has a central registry to resolve URLs to the current location of the resource. It is the underlying infrastructure for handle-based systems like DOI and DSpace.

- ARK (Archival Resource Key) — A decentralised PID scheme where any organisation that registers for a Name Assigning Authority Number (NAAN) can use their own metadata standard or conventions, resolver system and other ARK features, as well as develop and adhere to their own PID practice policies. ARKs are used by libraries, museums and government agencies worldwide.

Digital Object Identifiers

Contributors who allow LDaCA to make their data collections available through the portal can use the PIDs they have if they already follow a specific PID practice. However, if it is their first time obtaining a PID, we recommend DOIs as they are likely obtainable through a university library or institutional research repository. This has been the pattern with collections in the LDaCA portal to date. DOIs are also available through general-purpose repositories like Zenodo.

What is a DOI?

DOI stands for Digital Object Identifier, a PID which is in fact a digital identifier of an object, rather than an identifier of a digital object (DOI Key Facts). The DOI System was launched in 2000 by the International DOI Foundation (IDF), a not-for-profit organisation that functions as the governing body.

DOI Registration Agencies (RAs) all over the world offer services for registering DOIs and community-specific metadata. University libraries and institutional research repositories can be members of an RA (e.g. DataCite in Australia) which allows them to create (or mint) and register DOIs for their organisation.

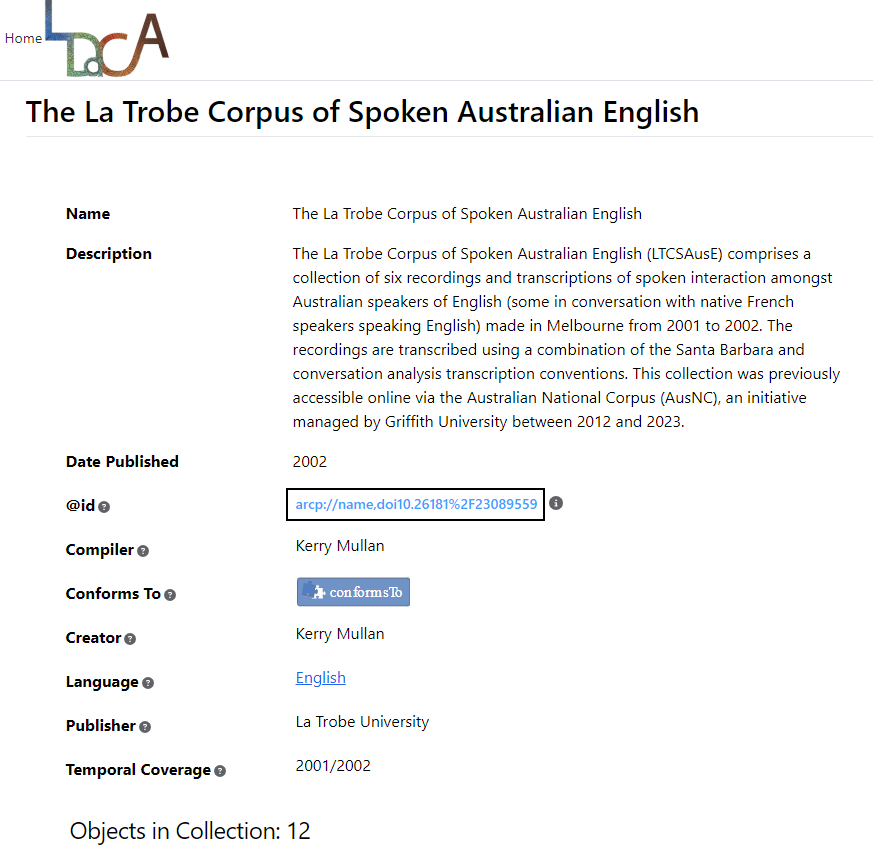

Here’s an example of a DOI for a collection available via the LDaCA data portal:

- In the partial screenshot below of the record for the collection, the DOI number (10.26181/23089559) is part of the collection’s @id. The full @id value is arcp://name,doi10.26181%2F23089559 and the last part of this is the DOI (the slash which separates parts of the DOI is represented by the encoding %2F here).

Image Source: LDaCA

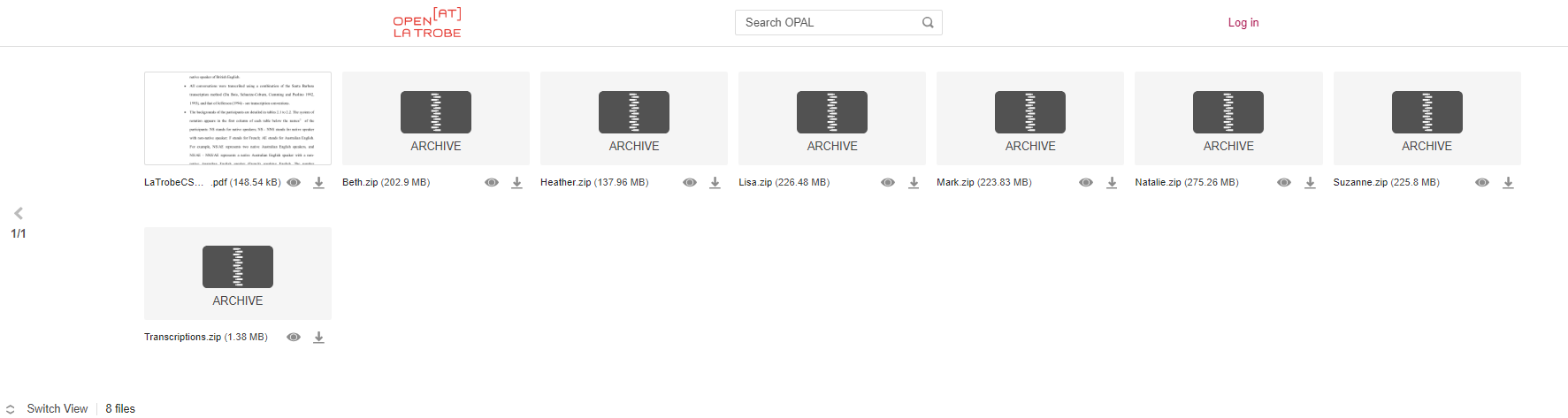

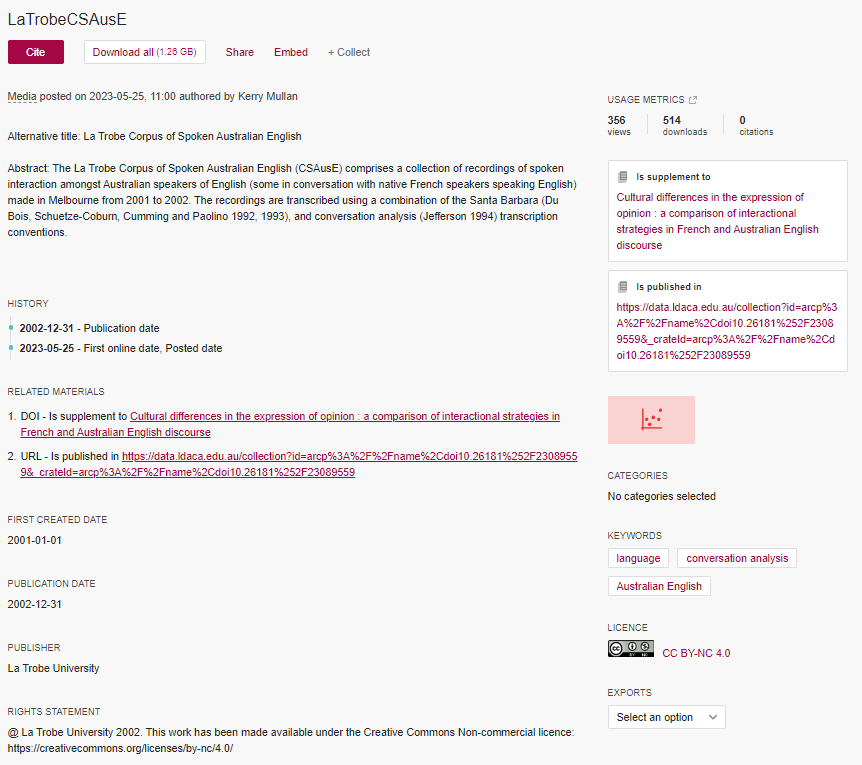

- The DOI resolves to an item in La Trobe University’s institutional repository. The content of the collection is available here, but there are also links to the record in the LDaCA portal which includes the DOI.

Image Source: LDaCA

Image Source: LDaCA

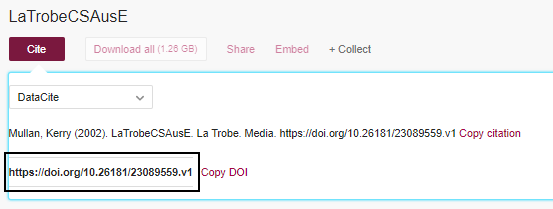

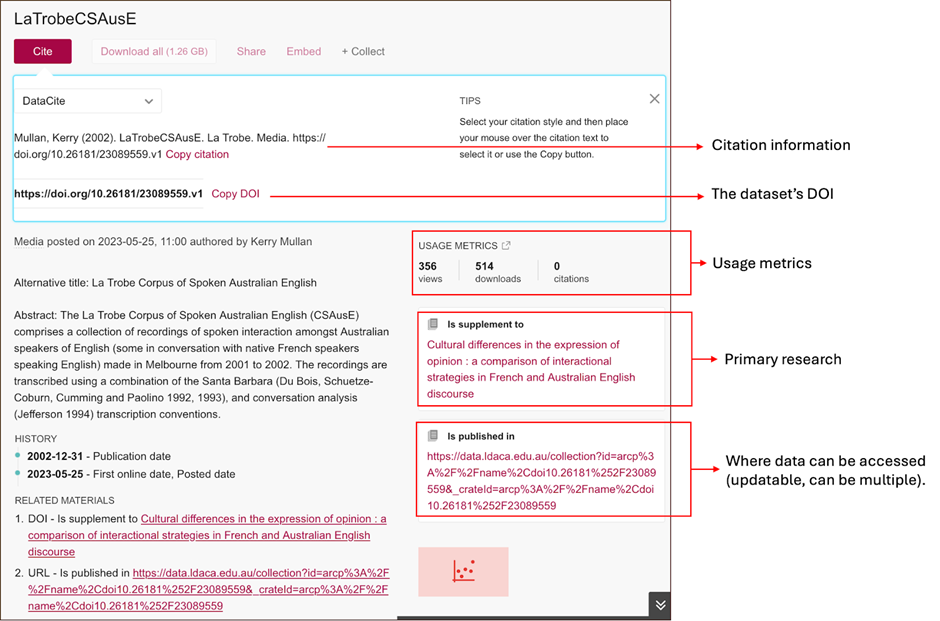

- Clicking the Cite button on the La Trobe repository page shows the DOI link in its full form:

Image Source: LDaCA

The DOI link is comprised of three parts:

| Resolver service | Prefix (the assigning body) | Suffix (the resource) |

|---|---|---|

| https://doi.org/ | 10.26181 | 23089559.v1 |

Why should my data collection have a DOI?

A review of the uptake of PID systems from the late 1990s to the late 2010s reported that DOIs are, for several good reasons, the most widely adopted PIDs in research data repository systems (Klump & Huber 2017). DOIs follow a standardised system: there is a syntax specification for the DOI name construction which is followed by all registrars, providing consistency across the board. The Handle System, a trusted and long-established digital infrastructure, is the DOI system’s resolution component providing reliability and persistence in the findability of research objects.

Another notable characteristic of the DOI system is its well-developed social infrastructure. The IDF develops and enforces rules and policies for the maintenance of records and for managing the division of responsibilities between RAs, RA members and DOI users. As a consequence, DOIs promote good data governance practices. Apart from the act of obtaining a DOI, the associated responsibilities of creating and recording accurate and rich metadata, ensuring that the DOI record is updated through location and data changes, and providing clear data reuse and access terms, enlighten data owners and stewards about some of the practicalities of data governance.

The DOI system’s underlying infrastructure supports interoperability across different platforms and systems. For example, DataCite’s “Add to ORCID Record” feature allows a researcher to manually claim a DOI of their work and link it to their ORCiD record (DataCite 2024). Data repositories can use DOIs to track usage metrics such as views, downloads and citations, which also informs data owners as to how researchers engage with the data.

Below is a screenshot of a section of the DOI landing page for the La Trobe Corpus of Spoken Australian English with some of the key information highlighted and annotated. The DOI was issued by DataCite via the La Trobe University Library’s DOI service.

Image Source: LDaCA

How do I get a DOI for my data collection?

We have an article about this topic on our website — see Obtaining a DOI.

What format(s) should my data files be in before I share them with LDaCA?

We understand that the choice of file formats during data planning and collection can be influenced by factors like research team decisions, discipline-specific norms, software-hardware compatibility and equipment funding. Although LDaCA's data migration experts can work with your data in any provided format, file formats that are easily shareable and reusable include:

- Text — TXT, PDF, (DOC/DOCX)

- Tabular data (which may include text) — CSV, (XLS/XLSX)

- Audio — WAV, MP3

- Video — MP4.

Bracketed formats are proprietary and therefore less sustainable.

References

Australian Research Data Commons. 2024. Australian national Persistent Identifier (PID) strategy 2024. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.10656275.

Chapekis, Athena, Samuel Bestvater, Emma Remy and Gonzalo Rivero. 2024. When Online Content Disappears. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/data-labs/2024/05/17/when-online-content-disappears/. (4 July, 2024).

DataCite. 2024. Add a DOI to Your ORCID Record. DataCite Support. https://support.datacite.org/docs/orcid-claiming. (4 July, 2024).

Klump, Jens & Robert Huber. 2017. 20 Years of Persistent Identifiers – Which Systems are Here to Stay? Data Science Journal 16. 09. https://doi.org/10.5334/dsj-2017-009.

Further reading

Car, Nicholas N. J., Pavel Golodoniuc & Jens Klump. 2017. The Challenge of Ensuring Persistency of Identifier Systems in the World of Ever-Changing Technology. Data Science Journal 16. 13. https://doi.org/10.5334/dsj-2017-013.

Kunze, John & Richard Rodgers. 2008. The ARK Identifier Scheme. UC Office of the President: California Digital Library. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9p9863nc. (4 July, 2024).