by Dr Julia Colleen Miller

For nearly ten years, I have been officially working as a Data Manager. I say officially because having worked on collaborative research projects and earning a PhD in Linguistics, within the context of an endangered language documentation collaborative project, I’ve been managing other people’s data, as well as my own, since I was a fledgling academic in the early 2000s.

I am based at the Australian National University (ANU), and since mid-2023, I’ve been working as the senior data manager for the Language Data Commons of Australia (LDaCA). Prior to this, I worked for the ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language (CoEDL), who could offer a eight year data manager position, very generous in a field where contracts often last only two or three years. It was at CoEDL where I first took on this academic-adjacent role, focusing on bolstering research and research infrastructure. It was also the first time I had heard of such a position becoming available that addressed the data management and archiving needs of those actively recording or assembling cultural heritage data. Such data includes tabular data, text corpora, collections of songs and music, ethnographic interviews, elicited linguistic content, oral histories, traditional narratives and lexicons, and can be in different formats, such as text, video, audio, image, film, magnetic tape and digital files.

The best part of this CoEDL role was that the Pacific and Regional Archive for Digital Sources in Endangered Cultures (PARADISEC), where I had been running the ANU unit since 2010, was going to be the main repository for CoEDL, and the two roles of archivist and data manager would be fundamentally intertwined. I had finally found my calling!

The day-to-day of data management and archiving

At CoEDL, my primary responsibility was to help facilitate the data management and subsequent archiving of materials collected by CoEDL members and affiliates from institutions such as ANU, The University of Queensland, The University of Melbourne, Western Sydney University (WSU), as well as by the broader global research communities. This involved managing a continuous flow of enquiries from new and continuing researchers, offering guidance, and overseeing the entire data management and archiving processes. My aim was to ensure that valuable research data was preserved and made:

- accessible for future research

- available to the people and communities recorded, as well as to their descendants.

Most days, in-person or over Zoom, I met with depositors to:

- guide them through the process of describing their data for their own research databases, making eventual archiving much easier

- discuss appropriate file formats

- find or create collaborative workspaces for CoEDL students, staff and their external collaborators

- develop data access protocols, refining conditions of access for archived collections

- offer file transfer options, ensuring secure data transmission

- inform researchers of other archiving alternatives if PARADISEC was not the best fit for their material.

Over the years, I have tried to make the data management and archiving processes more efficient and helpful by creating archiving guides. Originally, these were static PDF files available on the CoEDL website; however, as they needed to be dynamic sources of information for rapidly changing technologies, they are now a series of webpages.

Image Source: Dr Julia Colleen Miller

Managing the PARADISEC ANU unit

In my concurrent role as manager of the ANU unit of PARADISEC, I oversaw a wide range of digitisation and archiving activities, ensuring that important cultural materials were preserved and accessible for current and future use.

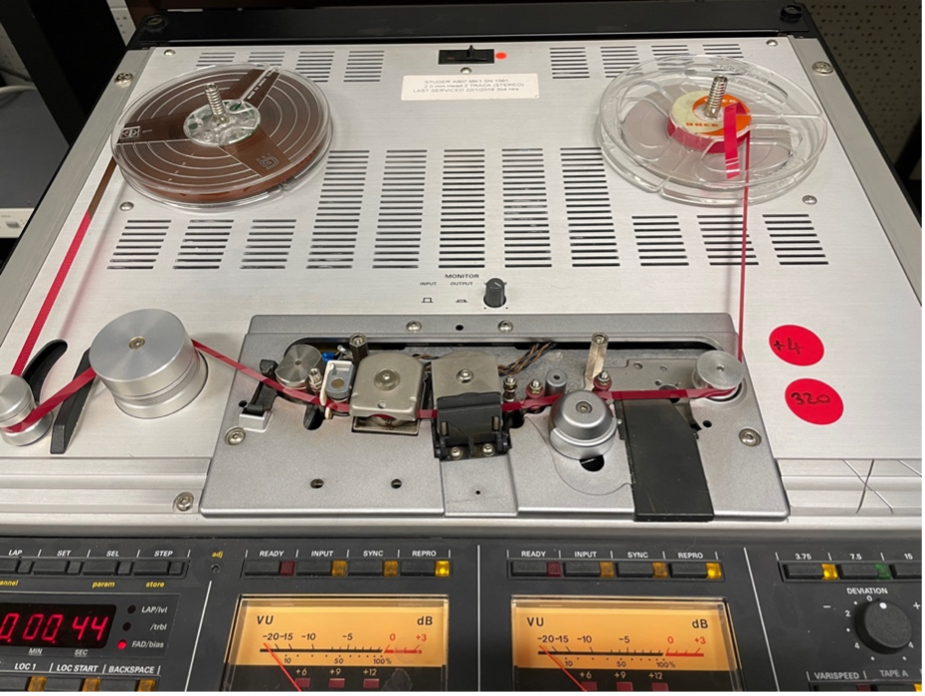

Digitising analogue materials

We often receive magnetic tape audio (cassette and reel-to-reel tapes) and field notebooks to archive. Engaging with legacy formats is equal parts exciting and challenging. The challenging parts are:

- finding and maintaining the necessary playback devices

- dealing with damaged or mouldy materials

- creating functional, evolving workflows

- adhering to standards set by digital preservation’s peak bodies.

…but the rewards are legion. There is nothing like hearing voices recorded decades ago, and then sharing those recordings with descendants of those speakers! It’s also a great feeling to make available rare language material by digitising the items, and then engage with young researchers to help enrich the descriptions of the content. Even more so if it helps them with their research topics.

Some of the digitising tasks we conducted during this time for CoEDL researchers and general PARADISEC depositors were:

- digitising audio cassettes and reel-to-reel tapes, performing all necessary post-production editing to prepare for archiving

Image Source: Dr Julia Colleen Miller

- photographing tapes and tape boxes containing written metadata on their labels or inserts found within; these images then accompanied the audio files in the archive

Image Source: Haoyi Li

- digitising manuscripts and field journals, ensuring high-quality reproduction.

Image Source: Dr Julia Colleen Miller

It is very satisfying knowing that by digitising these items, we helped make available legacy recordings brought to us by retiring researchers, small regional cultural institutions, and those found in our very own university archives.

If you are interested in our workflows for audio digitisation or manuscript and field note image capture, you can find more information below:

Handling born-digital files

Of course, we are now living in a time where digital recording devices of all kinds are all around us, making content creation very easy. With this easy access to quality recorders for use in the field, people have the freedom to collect as much data as needed to address their research questions. We receive hundreds (sometimes thousands) of digital files each week to help manage, and eventually, archive.

Some activities involved in managing born-digital files are:

- receiving files and creating detailed inventories of them — a critical step in ensuring all files are looked after and that quality checking can be logged

- resampling audio, transcoding image and video files to archival formats and managing the transfer to PARADISEC for archiving

- devising solutions for problematic video formats and liaising with commercial service providers and other institutions for help when needed.

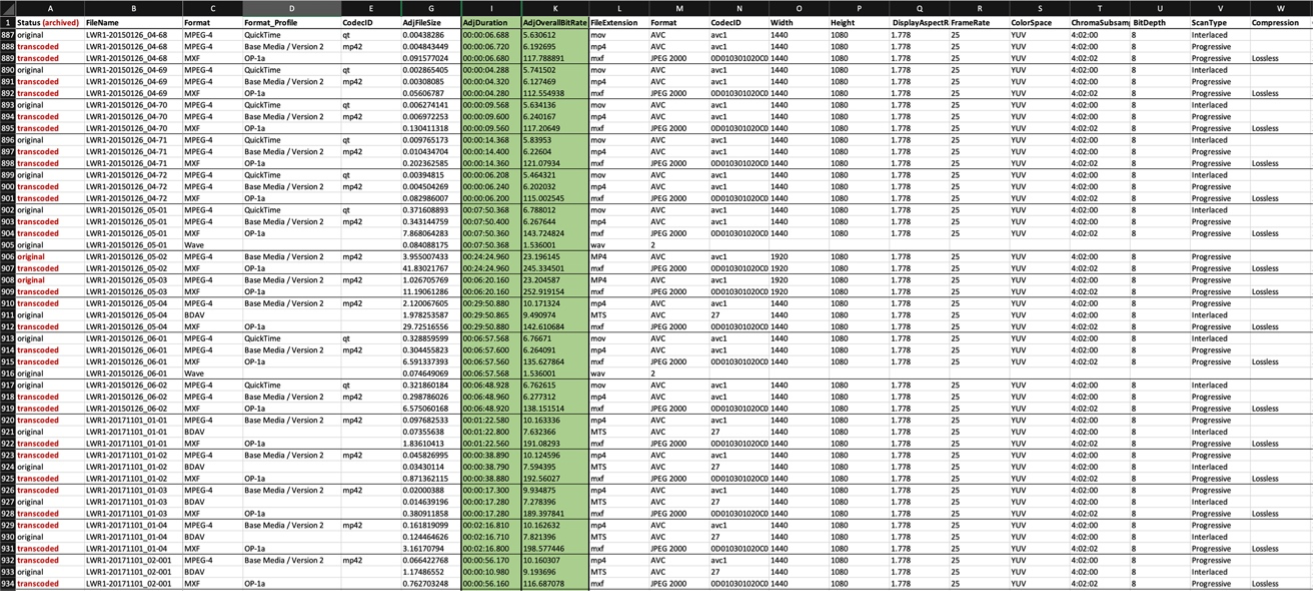

Below is an image of an inventory spreadsheet containing the structural metadata of thousands of files that went into a single collection: Lauren Reed’s Western Highlands Sign Languages.

Image Source: Dr Julia Colleen Miller

Creating an inventory like this informed me as to how to proceed in transcoding tasks, based on the format and specifications of the files. Also, I could compare details of the output files to the originals, thus helping with quality checks. As I worked through the files, I could keep track of my progress by marking which ones had been transcoded and were ready to send to the archive. This task took months to complete, so it was important to be able to pick up each day right where I had left off on the previous day.

If you are interested in learning how to batch extract this type of metadata from media files, visit the page Quality control of audio and video files from PARADISEC’s archiving guides and technical workflows.

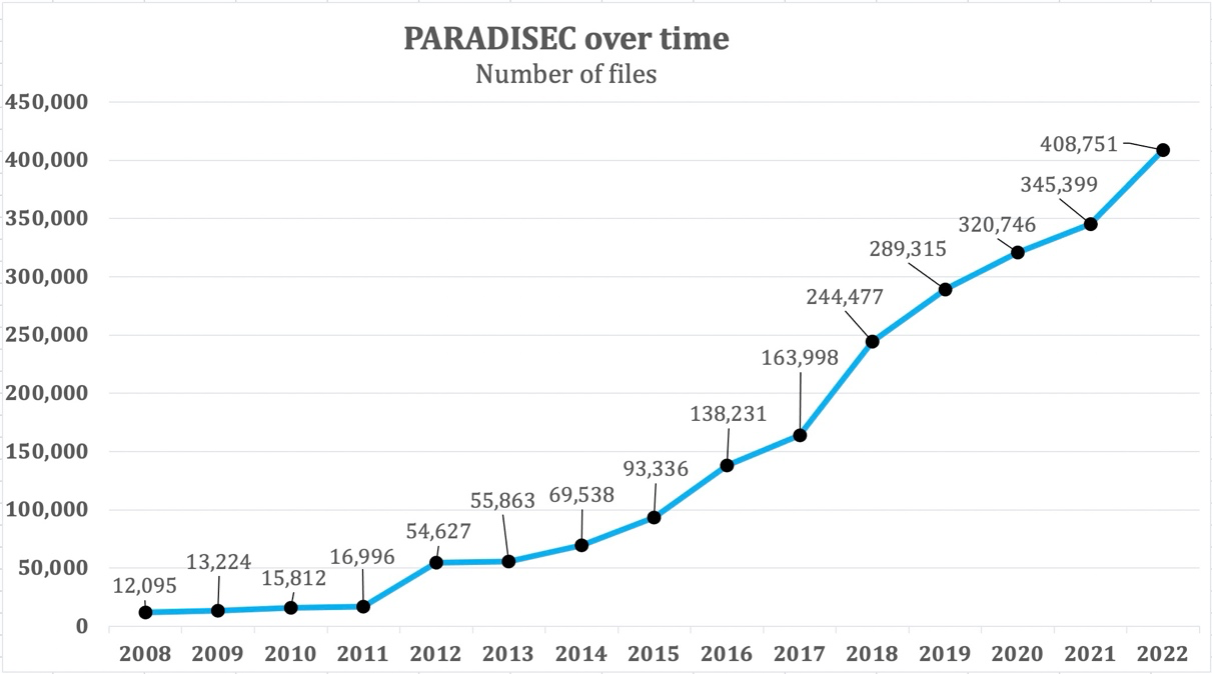

Over the life of CoEDL, we monitored the annual growth of files added to PARADISEC. The following graphic shows the period from 2008 to 2022. Note: CoEDL was active between November 2014 and December 2022.

Image Source: Dr Julia Colleen Miller

Notice the increase in files starting in 2015. It was at this time I received research assistant (RA) support from CoEDL to help manage the influx of data. Over the years, I supervised several RAs and volunteers, managing their day-to-day tasks and overseeing their professional growth.

By 2020, after refinements in our server connections and file transfer pipelines, we were sending a minimum of 500GB of audio-visual files to the archive every other day! I could never have achieved this without the support of the CoEDL RAs, Team Data: Jen Plaistowe, Tina Gregor, Melody Ross, Haoyi Li, Shubo Li, and our volunteer, Emma Cuppit.

Collaboration with cultural institutions in the region

Collaborating with other cultural institutions was a significant aspect of my roles at CoEDL and PARADISEC, allowing us to increase access to archived materials, enhance our archiving capabilities and share expertise. Below are two examples of collaborative projects.

ANU Pacific Research Archives

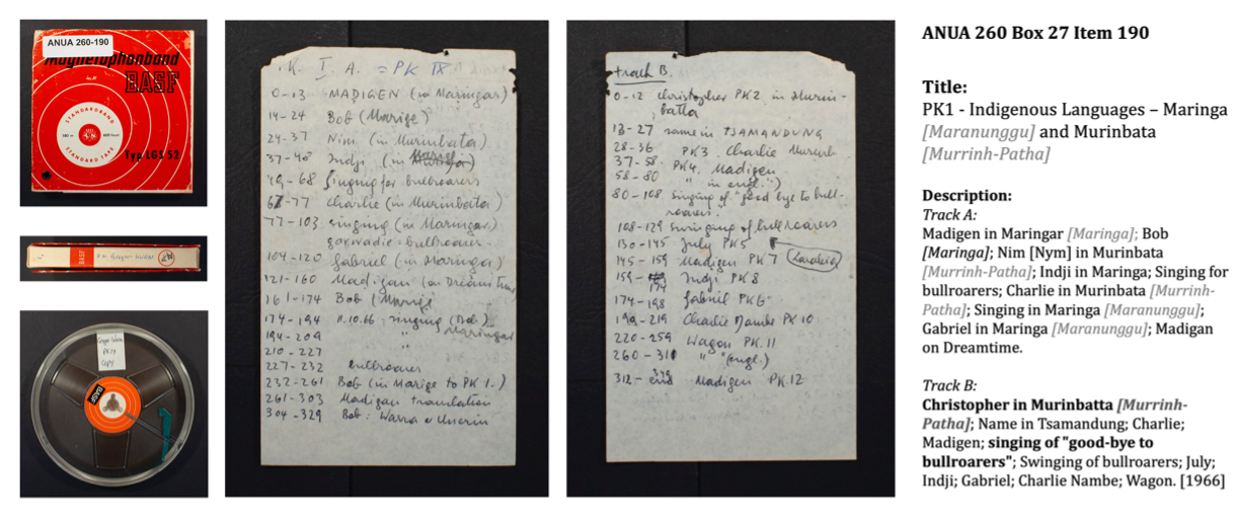

Occasionally, requests would come from ANU’s Pacific Research Archives staff, or directly from students and researchers, to digitise items collected across the Pacific which were housed in ANU’s archives. We targeted audio tapes and field notes for digitisation, enhancing ANU’s finding guides with detailed metadata. Typically, we archived these digital files in PARADISEC and shared links to new collections, or provided copies back to the Pacific Research Archives.

A notable project involved digitising select items from the Helen Groger-Wurm collection at ANU. Helen Groger-Wurm, an anthropologist active in the 1960s, focused on Northern Australia, particularly Eastern Arnhem Land bark paintings.

PARADISEC and CoEDL secured funding to digitise 26 audio tapes from this collection. This effort supported CoEDL PhD student Haoyi Li, who, due to COVID-19 restrictions, couldn’t conduct fieldwork in Arnhem Land when she was hoping to. Haoyi identified relevant items for her research, and we expanded the digitisation to include field notes alongside the audio tapes. This initiative enabled her to start her primary research remotely and gain valuable skills in archival engagement with legacy recordings, high-resolution image capture of field notes, open reel audio tape digitisation, metadata collection and archival record enrichment.

Image Source: Dr Julia Colleen Miller

The images below are from a tape digitised by Haoyi Li from the Helen Groger-Wurm collection in the Pacific Research Archives at ANU. The image shows that there is metadata written on the tape box and labels, as well as on the slip of paper found in the tape box. These tape-counter reference points to topics contained on the recording and the tape labels provided the title and description for the archive.

Image Source: Dr Julia Colleen Miller

AIATSIS, NLA and NFSA

We sometimes find items held in other cultural institutions, which we would like to digitise and add to existing collections in PARADISEC. For example, we identified items produced by the important 20th century Australian linguist Arthur Capell, including 168 reel-to-reel audio tapes of non-Australian language recordings found in the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) that we were able to digitise, and nearly 50 acetate discs and one magnetic wire recording found at the National Library of Australia (NLA). We enlisted the aid of the National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA) in digitising the discs and magnetic wire, as we did not have the facilities to handle those formats.

Below is an image of a Capell disc being digitised by the NFSA. This contains recordings of the parable of the Prodigal Son and the Lord’s Prayer in the Bilua language of the Solomon Islands. Listen to the recording via the Capell collection in PARADISEC.

Image Source: Gerry O'Neill

The next image is of the magnetic wire recording on its spool. This item contains narratives in languages of North and Central America, including Kiowa and Navajo. To hear these recordings, see the Capell collection.

Image Source: Dr Julia Colleen Miller

Managing large-scale, short-term projects

In addition to my regular duties as data manager and digital archivist, I was sometimes tasked with overseeing the management of large-scale projects that required careful planning, coordination and implementation.

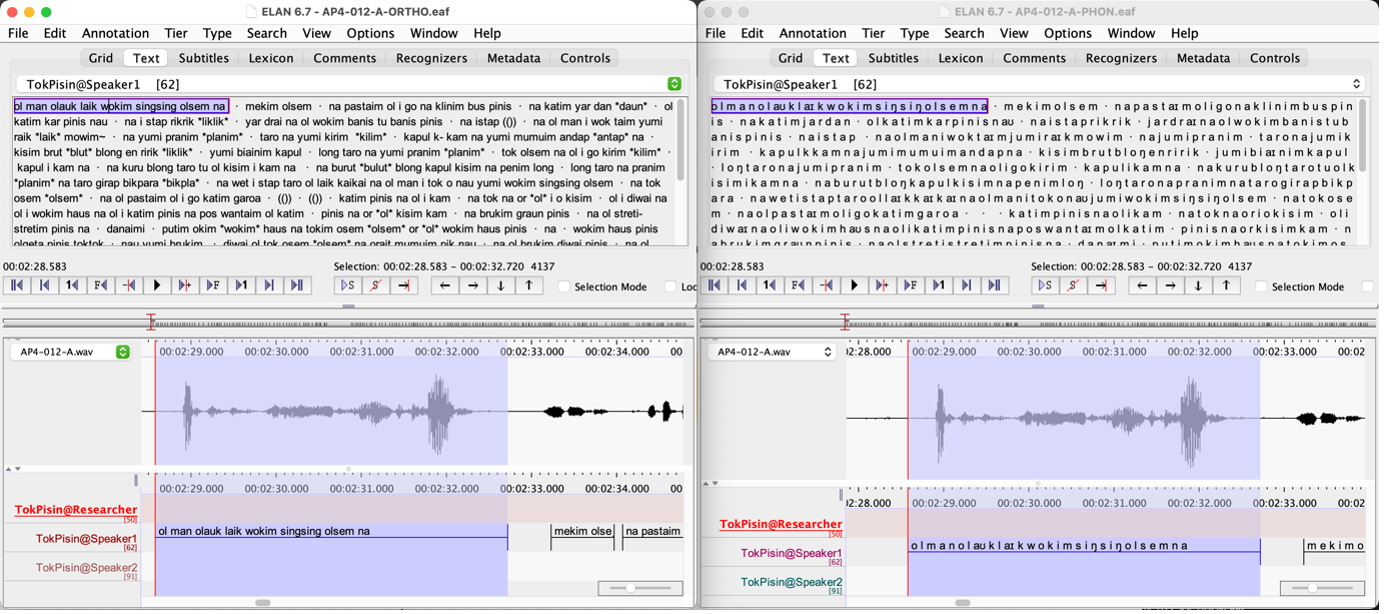

Phonemic modelling of Tok Pisin

The first was a three-year project between ANU and the Commonwealth Defence Science and Technology Group (DSTG) called ‘Phonemic Modelling of Tok Pisin'.

This project involved creating phonemic transcriptions of spoken Tok Pisin, the English-based creole which is a national language of Papua New Guinea. We retrieved open-access, untranscribed audio recordings of Tok Pisin held in PARADISEC and created rich time-aligned transcriptions, adding these back to their source collections, as well as providing these transcriptions to the DSTG.

Below are images of transcriptions in the ELAN transcription software. The recordings were made by Andy Pawley in the Kaironk Valley region of Papua New Guinea and are held in PARADISEC as collection AP4.

Image Source: Dr Julia Colleen Miller

Some tasks for this project included:

- targeting existing PARADISEC collections that held Tok Pisin content and preparing the audio for transcription

- liaising with DSTG on technical details to ensure mutual understanding and alignment

- creating detailed workflows and timelines to meet project deadlines

- hiring, training and managing a transcription team, including three Tok Pisin speakers

- delegating tasks to team members and monitoring their progress

- writing annual reports and conducting team debriefing meetings to gather feedback and adjust workflows as needed.

In the end, PARADISEC gained rich transcriptions of previously untranscribed Tok Pisin audio held within the archive. Additionally, we were able to employ and train two ANU PhD students and one of PARADISEC’s archivists, Steven Gagau, all fluent Tok Pisin speakers, in using the ELAN software for creating the time-aligned transcriptions.

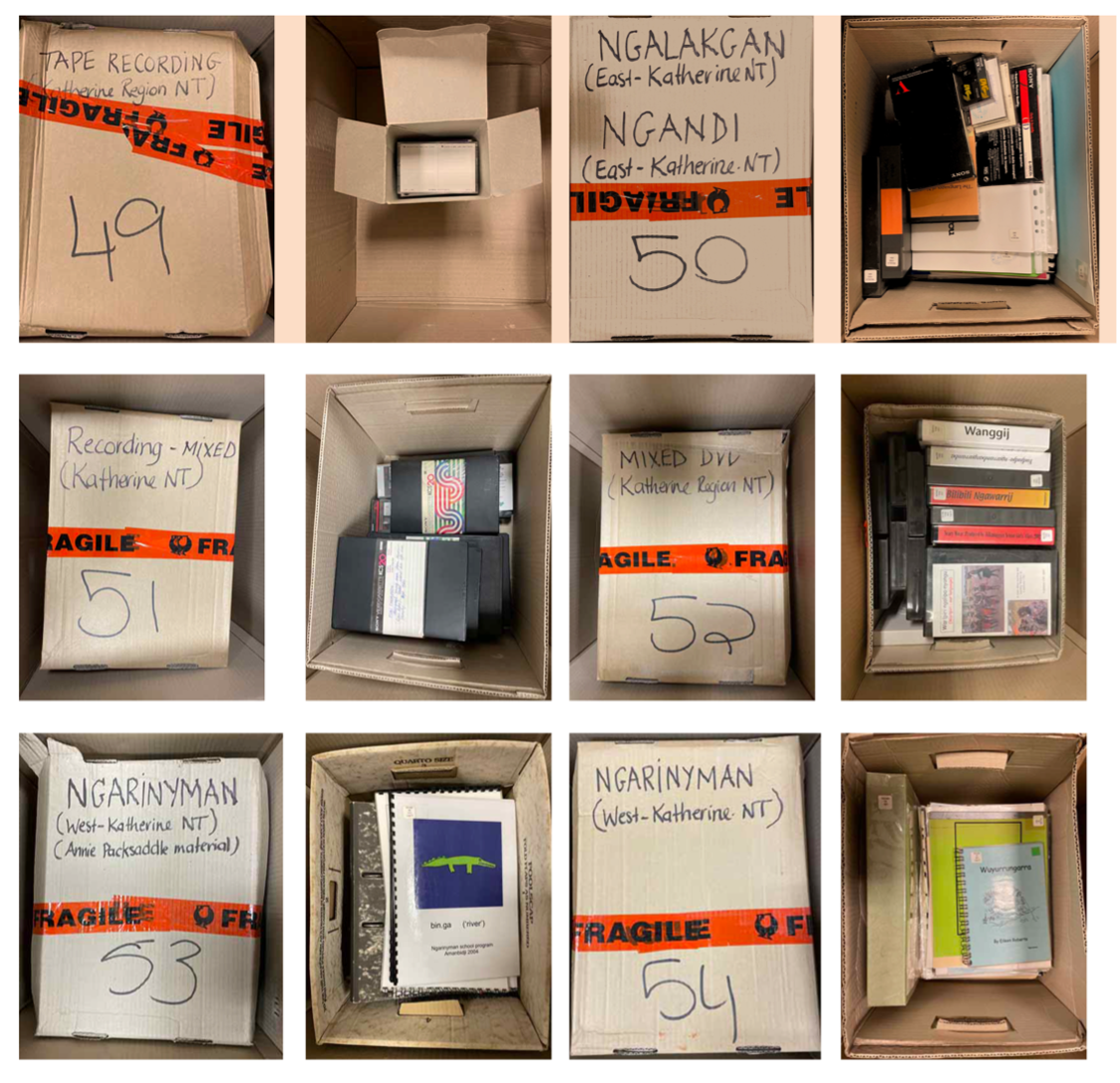

Digitising language material from the Katherine region

Another significant project involved the secure storage of audio-visual materials and manuscripts from the Katherine region of Australia during renovations at their language centre. CoEDL Deputy Director Jane Simpson (ANU) and CoEDL CI Caroline Jones (WSU) tasked my team with storing, inventorying and overseeing the digitisation of materials contained in 42 shipping boxes from Mimi Arts & Crafts, previously known as Diwurruwurru-jaru (Katherine Regional Aboriginal Language Centre).

Image Source: Dr Julia Colleen Miller

Each box contained two smaller boxes with language-learning materials and cultural recordings created with Elders, primarily in the 1990s and 2000s. We expanded on an earlier inventory, creating a comprehensive list to facilitate digitisation and the eventual return of original items and digitised files to the Katherine Region.

Image Source: Dr Julia Colleen Miller

Key aspects of the project included:

- developing a detailed inventory workflow and training a new RA

- collaborating with stakeholders, such as Caroline Jones, Jane Simpson, other invested researchers, Mimi Arts & Crafts representatives, AIATSIS, commercial digitisation providers, and loads of volunteer facilitators

- providing progress reports and maintaining communication with stakeholders

- facilitating the temporary removal and return of items for early digitisation efforts

- managing the repackaging and distribution of boxes as digitisation progressed.

Service to the archiving community

My contributions to the archiving community extended beyond CoEDL, through presentations, training modules and active participation in professional organisations. I have participated in conferences and workshops, representing CoEDL and PARADISEC while discussing best practices in archiving and data management. I also focused on developing training sessions aimed at enhancing digitisation techniques, metadata management and workflow optimisation for fellow archivists.

As a member of the International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives (IASA), I continue to contribute to their Technical Committee, where I can participate in discussions that influence the development of digital preservation standards. I also contribute to the creation of guidelines for born-digital video, aiming to ensure they are relevant to current technological advancements and archival needs.

I have collaborated with Charles Sturt University’s Master of Information Studies program, guiding a student through an approved curriculum I developed that aimed to bridge academic learning with practical skills. These teaching materials have been used again for students from the University of Manchester’s Master of Arts programs in Digital Media, Culture and Society, and in Library and Archive Studies under the tutelage of my PARADISEC colleague, Nick Ward.

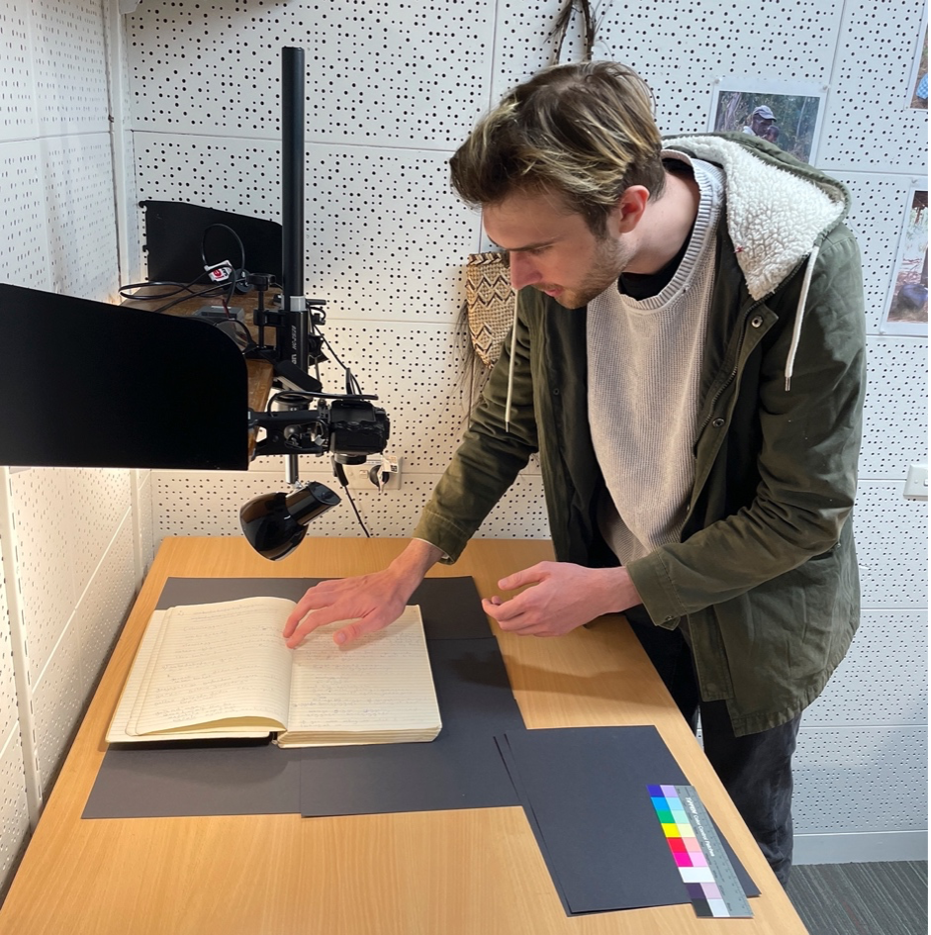

During ANU’s COVID-19 lockdown, I designed a 10-week online training module to accommodate my newly hired RAs, providing foundational knowledge in digitisation and archiving techniques. This online training was extended to ANU’s Summer Scholar interns, who were also missing out on activities due to lockdown. We focused on audio and manuscript digitisation practices, as well as introducing them to the history of digital language archives. When the lockdown was lifted, we followed up with hands-on training. One of the interns, a PhB student in Linguistics, Daniel Majchrzak (seen in the image below), has been trained in high-resolution image capture of manuscripts and fieldnotes and is now working in our studio to digitise the papers of Luise Hercus.

Image Source: Dr Julia Colleen Miller

Final thoughts

Data management is an integral element of institutional research infrastructure. It often falls within that fluid space between the roles of academic and professional staff — within what is called the Third Space in academia (to read more on this topic, take a look at "Reconstructing Identities in Higher Education: The rise of ‘Third Space’ professionals", by Celia Whitchurch, 2013). Many of the activities carried out as Data Manager for CoEDL, and now for LDaCA, were designed to assist in educational development and knowledge exchange, as well as to promote public engagement and outreach. These tasks not only assisted students and academic researchers to better conduct their research enquiries and safeguard their work, but they also facilitated activities that directly reinforced the academic missions of our universities.

I love the work that I do. I feel lucky to be a part of so many diverse projects, even if it just involves:

- helping people name their files or store their research materials securely

- making an inventory of cassette tapes to be digitised

- connecting students to archival records of a language they are thinking about for their PhD research

- helping researchers

repatriaterematriate recordings in a format that is accessible to the people who have been recorded, and to their descendants.

Every day is a new and exciting challenge!